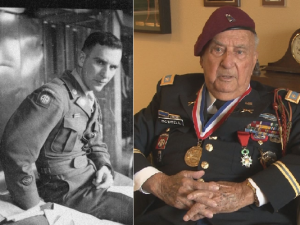

Remembering WWII paratrooper Henry “Duke” Boswell

BY CHUCK | DEC 1, 2015

IN: INSPIRATIONAL, U.S. ARMY, VIDEO, VINTAGE PHOTOS, WWII

World War II Army veteran Maj. Henry “Duke” Boswell has died. He was 91.

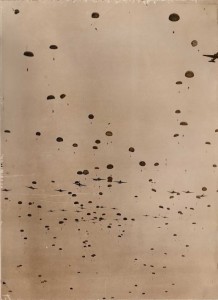

Boswell was a survivor of combat in the Battle of the Bulge and helped liberate a concentration camp in Germany. He made four combat parachute jumps with the 82nd Airborne in Sicily, Italy, Normandy and The Netherlands. Here is his story…

He leaned out of the open door of the United States Army C-47 plane, flying 600 feet above the water, and as far as he could see, were ships.

World War II Army veteran Maj. Henry “Duke” Boswell has died. He was 91.

Boswell was a survivor of combat in the Battle of the Bulge and helped liberate a concentration camp in Germany. He made four combat parachute jumps with the 82nd Airborne in Sicily, Italy, Normandy and The Netherlands. Here is his story…

He leaned out of the open door of the United States Army C-47 plane, flying 600 feet above the water, and as far as he could see, were ships.

Big ships and little ships floated below him. Above him, fighter planes, bombers, and cargo planes carrying American soldiers.

Big ships and little ships floated below him. Above him, fighter planes, bombers, and cargo planes carrying American soldiers.

It was midnight, June 6, 1944, and then-Sergeant Henry ‘Duke’ Boswell was preparing to jump into Ste. Mere Eglise, just seven miles from the infamous beaches of Normandy, France.

“We were told when the green light goes on, meaning jump, you better get out of that plane as fast as you can, because we got about a minute before we’re back over the ocean. And over the front lines,” Boswell recalled from an easy chair in the living room of his apartment in Colorado Springs. The faintest of smiles crosses his lips as he chuckled, “We got out of there rather fast.”

Big ships and little ships floated below him. Above him, fighter planes, bombers, and cargo planes carrying American soldiers.

It was midnight, June 6, 1944, and then-Sergeant Henry ‘Duke’ Boswell was preparing to jump into Ste. Mere Eglise, just seven miles from the infamous beaches of Normandy, France.

“We were told when the green light goes on, meaning jump, you better get out of that plane as fast as you can, because we got about a minute before we’re back over the ocean. And over the front lines,” Boswell recalled from an easy chair in the living room of his apartment in Colorado Springs. The faintest of smiles crosses his lips as he chuckled, “We got out of there rather fast.”

When Boswell enlisted in the Army at the age of 16, and had forged his mother’s name on his enlistment papers. He earned $30 a month. The year was 1940 and he was tired of picking cotton for a dollar a day in his home state of North Carolina.

The year he should have graduated high school, he instead joined the National Guard and prepared for war.

“They told us one day we were going to be called on active duty for one year,” Boswell said.

Instead, Boswell would remain on active duty until the end of World War II, and continue his service through the Korean War, before retiring in 1963.

While training at Fort Jackson in South Carolina, Boswell asked his commander for a transfer. His commander told him he could move to an airborne unit in two weeks.

“They told us if we qualified you would get $50 a month extra, for jumping,” Boswell said, “So I said, ‘Sign me up for the airborne!’

When Boswell enlisted in the Army at the age of 16, and had forged his mother’s name on his enlistment papers. He earned $30 a month. The year was 1940 and he was tired of picking cotton for a dollar a day in his home state of North Carolina.

The year he should have graduated high school, he instead joined the National Guard and prepared for war.

“They told us one day we were going to be called on active duty for one year,” Boswell said.

Instead, Boswell would remain on active duty until the end of World War II, and continue his service through the Korean War, before retiring in 1963.

While training at Fort Jackson in South Carolina, Boswell asked his commander for a transfer. His commander told him he could move to an airborne unit in two weeks.

“They told us if we qualified you would get $50 a month extra, for jumping,” Boswell said, “So I said, ‘Sign me up for the airborne!’

Boswell was assigned to the 505 Parachute Regiment, which was absorbed by the 82nd Airbone Division in Fort Bragg.

Six weeks of training. Airborne soldiers ran everywhere, even to breakfast.

“Everything was aimed at eliminating the ones who couldn’t do it,” he said.

In all, Major Boswell made 105 airborne jumps, many of them in a parachute he packed himself.

‘We just kept fighting’

From Fort Bragg, the 82nd shipped out in the spring of 1943, headed to the coast of Casablanca.

The night of July 10, Boswell and G Company jumped into Sicily with 146 men.

“Our job was to grab crossroads and bridges that led to the beach, and keep more Germans from getting to the beach to reinforce their troops. So, we had to hold whatever position we had until the people from the beach got to us,” he remembered, “We thought we’d be pulled back, but they didn’t [pull us back]. They put us in front and we just kept fighting.”

The next night, the 504th jumped in to reinforce G Company, flying low in C47s over oceans stocked with U.S. ships.

Boswell was assigned to the 505 Parachute Regiment, which was absorbed by the 82nd Airbone Division in Fort Bragg.

Six weeks of training. Airborne soldiers ran everywhere, even to breakfast.

“Everything was aimed at eliminating the ones who couldn’t do it,” he said.

In all, Major Boswell made 105 airborne jumps, many of them in a parachute he packed himself.

‘We just kept fighting’

From Fort Bragg, the 82nd shipped out in the spring of 1943, headed to the coast of Casablanca.

The night of July 10, Boswell and G Company jumped into Sicily with 146 men.

“Our job was to grab crossroads and bridges that led to the beach, and keep more Germans from getting to the beach to reinforce their troops. So, we had to hold whatever position we had until the people from the beach got to us,” he remembered, “We thought we’d be pulled back, but they didn’t [pull us back]. They put us in front and we just kept fighting.”

The next night, the 504th jumped in to reinforce G Company, flying low in C47s over oceans stocked with U.S. ships.

The U.S. Navy had been taking heavy fire from the Germans all night. When the Americans began jumping in to Sicily, tragedy struck. Uninformed U.S. ships opened fire on their own men.

“The entire navy opened up. They shot down 28 planes, 300 men of our own. Killed our own troops,” Boswell said as his bottom lip trembled, “It was a bad scene.”

The next jump for the 82nd, into Salerno, would earn the liberation of a German-held city, Naples.

Boswell’s unit helped free the city on Oct 1, 1943, and held it until November.

The U.S. Navy had been taking heavy fire from the Germans all night. When the Americans began jumping in to Sicily, tragedy struck. Uninformed U.S. ships opened fire on their own men.

“The entire navy opened up. They shot down 28 planes, 300 men of our own. Killed our own troops,” Boswell said as his bottom lip trembled, “It was a bad scene.”

The next jump for the 82nd, into Salerno, would earn the liberation of a German-held city, Naples.

Boswell’s unit helped free the city on Oct 1, 1943, and held it until November.

“The planes had to circle for a long time. We took off on the night of five June, but the weather was so bad they called it off,” Boswell recalled clearly, even though he had just celebrated his 90th birthday in 2014 when this interview was conducted.

At Ste. Mere Eglise, France, Boswell’s company was assigned to hold two bridges, and block and hold the city as they waited for ground troops to reinforce them the next morning.

They were the only company to drop on target. His company commander landed 20 miles away.

“Even though you jump with 2,000 troopers, when you land you’re by yourself,” Boswell said. He was assigned as a radioman.

American troops landed at 6:30 p.m., Boswell recalls, his memory sharp as ever, seven decades later. “We had the Germans out by 4:30 p.m. and raised the flag over [St. Mere Eglise’s] City Hall.”

The same flag his company raised in Naples.

“The planes had to circle for a long time. We took off on the night of five June, but the weather was so bad they called it off,” Boswell recalled clearly, even though he had just celebrated his 90th birthday in 2014 when this interview was conducted.

At Ste. Mere Eglise, France, Boswell’s company was assigned to hold two bridges, and block and hold the city as they waited for ground troops to reinforce them the next morning.

They were the only company to drop on target. His company commander landed 20 miles away.

“Even though you jump with 2,000 troopers, when you land you’re by yourself,” Boswell said. He was assigned as a radioman.

American troops landed at 6:30 p.m., Boswell recalls, his memory sharp as ever, seven decades later. “We had the Germans out by 4:30 p.m. and raised the flag over [St. Mere Eglise’s] City Hall.”

The same flag his company raised in Naples.

For two long days troops on the beaches of Normandy fought to make it to Boswell’s location.

They did.

And then they fought, together, for 33 days straight.

Boswell returned to France. Germans had broken through American lines in the Ardennes Forest, Belgium.

“In the mountains, in a place we thought was quiet. But, somehow, Hitler had managed to amass four to five-thousand troops without us knowing. And when they attacked, our front lines were thin – and they just ran right over,” Boswell’s keen memory could still pinpoint the details of the largest land battle the United States has ever been involved in.

For two long days troops on the beaches of Normandy fought to make it to Boswell’s location.

They did.

And then they fought, together, for 33 days straight.

Boswell returned to France. Germans had broken through American lines in the Ardennes Forest, Belgium.

“In the mountains, in a place we thought was quiet. But, somehow, Hitler had managed to amass four to five-thousand troops without us knowing. And when they attacked, our front lines were thin – and they just ran right over,” Boswell’s keen memory could still pinpoint the details of the largest land battle the United States has ever been involved in.

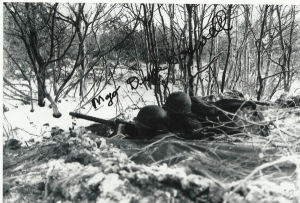

He fought in The Battle of the Bulge for thirty frozen days and nights.

“We probably had, we just had thousands of troops that were lost. Killed. Or ran over. Or captured,” Boswell’s eyes, clear blue, had clouded ever so slightly, “Thousands and thousands they captured.”

The weather was so bitter planes couldn’t fly. 500,000 troops were fighting on each side.

Sergeant Boswell’s feet turned black.

“It was the worst winter they had in 50 years. The snow in places was waist deep. You’d come to some creek, and all you could do was wade across it. We didn’t have winter equipment, hadn’t had time to get it,” Boswell said, “We probably lost more men from trench foot and frozen foot than we did to the enemy.”

He fought in The Battle of the Bulge for thirty frozen days and nights.

“We probably had, we just had thousands of troops that were lost. Killed. Or ran over. Or captured,” Boswell’s eyes, clear blue, had clouded ever so slightly, “Thousands and thousands they captured.”

The weather was so bitter planes couldn’t fly. 500,000 troops were fighting on each side.

Sergeant Boswell’s feet turned black.

“It was the worst winter they had in 50 years. The snow in places was waist deep. You’d come to some creek, and all you could do was wade across it. We didn’t have winter equipment, hadn’t had time to get it,” Boswell said, “We probably lost more men from trench foot and frozen foot than we did to the enemy.”

“We started in Sicily with 146 men. When the war ended, we were in Germany, we had 13,” Boswell paused, remembering his fallen brothers, “Each time we went into a battle we’d lose two, three, four, eight, ten,” Boswell’s voice trailed off and he took a brief moment of silence.

“You knew there were only two things that could happen. Either the war ended and you went home, or it didn’t end and you kept fighting. And you kept losing some of that 13 each battle, until it was down to you. You knew that was going to happen unless the war ended. That’s what we were fighting for then,” Boswell recounted his last days of the war.

“We started in Sicily with 146 men. When the war ended, we were in Germany, we had 13,” Boswell paused, remembering his fallen brothers, “Each time we went into a battle we’d lose two, three, four, eight, ten,” Boswell’s voice trailed off and he took a brief moment of silence.

“You knew there were only two things that could happen. Either the war ended and you went home, or it didn’t end and you kept fighting. And you kept losing some of that 13 each battle, until it was down to you. You knew that was going to happen unless the war ended. That’s what we were fighting for then,” Boswell recounted his last days of the war.

One of Boswell’s final stops before he returned home was in Ludvigslust, Germany.

“They had this big, beautiful castle with a beautiful park,” Boswell recalled.

It would be in front of that very castle, in that very beautiful park, that Boswell’s General, General James Gavin, would force the townspeople to bury thousands of dead.

Right outside the town was the Wobbelin concentration camp.

“I managed to get out there with my company commander. There were boxcars sitting there, loaded with bodies. In the barracks there were dead and dying both,” said Boswell.

G Company took over the camp, and General Gavin made the men of Ludwigslust dig graves for two hundred of the men, women, and children who lay dead or dying just outside their town.

“He laid a body by each grave and made every adult in town come and walk by those bodies. He made them look at them because they claimed they knew nothing about it, maybe they didn’t,” Boswell came home just a short time later.

One of Boswell’s final stops before he returned home was in Ludvigslust, Germany.

“They had this big, beautiful castle with a beautiful park,” Boswell recalled.

It would be in front of that very castle, in that very beautiful park, that Boswell’s General, General James Gavin, would force the townspeople to bury thousands of dead.

Right outside the town was the Wobbelin concentration camp.

“I managed to get out there with my company commander. There were boxcars sitting there, loaded with bodies. In the barracks there were dead and dying both,” said Boswell.

G Company took over the camp, and General Gavin made the men of Ludwigslust dig graves for two hundred of the men, women, and children who lay dead or dying just outside their town.

“He laid a body by each grave and made every adult in town come and walk by those bodies. He made them look at them because they claimed they knew nothing about it, maybe they didn’t,” Boswell came home just a short time later.

That would not be the end of his service. Boswell re-enlisted a year later and found himself fighting in Korea five years after that.

He was hit by a mortar blast in August 1950, shortly after deploying during The Korean War. He still carries shrapnel in his legs. He lost a part of his hand.

Eight months in a hospital, six months in a wheelchair. His service didn’t end there, either.

He remained in the Army until 1963.

He spent twenty years after that teaching sixth graders with a masters degree in education.

Major Henry Duke Boswell had seen terror, tragedy, and turmoil. He was a living piece of history in a population rapidly diminishing.

“I’ve asked soldiers, retirees and active duty what were you fighting for? And the answer always came back, ‘We don’t want these soldiers in our homes, we don’t want them in America. We want to keep the enemy away,” Boswell says.

That would not be the end of his service. Boswell re-enlisted a year later and found himself fighting in Korea five years after that.

He was hit by a mortar blast in August 1950, shortly after deploying during The Korean War. He still carries shrapnel in his legs. He lost a part of his hand.

Eight months in a hospital, six months in a wheelchair. His service didn’t end there, either.

He remained in the Army until 1963.

He spent twenty years after that teaching sixth graders with a masters degree in education.

Major Henry Duke Boswell had seen terror, tragedy, and turmoil. He was a living piece of history in a population rapidly diminishing.

“I’ve asked soldiers, retirees and active duty what were you fighting for? And the answer always came back, ‘We don’t want these soldiers in our homes, we don’t want them in America. We want to keep the enemy away,” Boswell says.

Duke Speaks

It had been over 70 years since Duke Boswell leaned out of that Army C47 plane, staring onto the beaches of Normandy.

He’d tell you his war stories, his memories of the Greatest Generation. He wouldn’t have told you he’s a hero.

“For me, I don’t consider myself a hero, I do the ones that we left. So many good friends that you’d made over two, three, four years maybe,” His voice quivered just a bit, “We did believe in what we were fighting for. In America. In our way of living.”

After a pause, Boswell continued, “I would do it over again.”

We are grateful for your sacrifices and service Duke. May you rest in peace brother, we shall carry on the fight from here.

It had been over 70 years since Duke Boswell leaned out of that Army C47 plane, staring onto the beaches of Normandy.

He’d tell you his war stories, his memories of the Greatest Generation. He wouldn’t have told you he’s a hero.

“For me, I don’t consider myself a hero, I do the ones that we left. So many good friends that you’d made over two, three, four years maybe,” His voice quivered just a bit, “We did believe in what we were fighting for. In America. In our way of living.”

After a pause, Boswell continued, “I would do it over again.”

We are grateful for your sacrifices and service Duke. May you rest in peace brother, we shall carry on the fight from here.